Congressional Briefing Explores the Impact of Education on Mortality

On July 27, the Population Association of America (PAA) held a congressional briefing, “Live Long and Prosper: The Impact of Education on Mortality,” which focused on the federal investments in longitudinal demographic research that have allowed researchers to identify and measure how educational attainment affects important life factors, including long-term health and mortality. COSSA joined PAA, a COSSA Governing Member, along with several other COSSA member organizations in sponsoring the briefing.

Sharing the latest findings with a standing-room-only audience, the panel of distinguished researchers included Robert M. Kaplan, Agency for Health Care Research and Quality and former director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR); Jennifer Karas Montez, Syracuse University; Ray K. Masters, University of Colorado at Boulder; and Vida Maralani, Yale University.

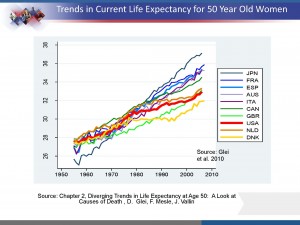

Robert Kaplan provided an overview and shared insight with staff on “Understanding the Relationship between Years of Education and Longevity.” He explained that the U.S. has been examining quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) since the late 1950s and 1960s. The data reveals that current life expectancy for 50-year-old women is deteriorating. He explained that between 1955 and 1980, life expectancy for U.S. women at age 50 stayed solidly in the middle of the group of peer countries.

Robert Kaplan provided an overview and shared insight with staff on “Understanding the Relationship between Years of Education and Longevity.” He explained that the U.S. has been examining quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) since the late 1950s and 1960s. The data reveals that current life expectancy for 50-year-old women is deteriorating. He explained that between 1955 and 1980, life expectancy for U.S. women at age 50 stayed solidly in the middle of the group of peer countries.

Kaplan noted that this trend was similar to that of other countries with the exception of Japan, which started out behind but made faster gains than the other countries throughout the period. After 1980, the pace of gains in the life expectancy for females aged 50 slowed for U.S. women along with those in Denmark and the Netherlands, while continuing at a fast pace among other countries. In the mid-1990s and beyond, the women in Denmark resumed making progress and in very recent years, Dutch women also began making faster gains. The U.S. is at the bottom on a list of 17 peer countries (Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, and the United States).

Kaplan highlighted the most recent data from the 2013 Institute of Medicine (IOM)/National Academies of Sciences (NAS) report, U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health, which found that the problem is longstanding and worsening. In 1980, U.S. life expectancy was about average among females and near the bottom for males. By 2006, however, life expectancy for both sexes had fallen to the bottom ranks. The report further found that U.S. male and female newborns can expect to lose approximately 1.4 years and 0.8 years of life, respectively, before age 50. Kaplan highlighted the fact that the U.S. losses due to premature death before age 50 are twice that of Sweden.

When it comes to education, Kaplan reported that U.S. educational attainment is slipping. U.S. preschool enrollment is lower than in most high-income countries. For U.S. adults of all ages, the U.S. ranks well in educational attainment, but other countries, including emerging economies, are outpacing the U.S. when it comes to graduation rates. In addition, while U.S. grade school students score above average in math, science, and reading, by age 15 U.S. students are found to have scores that are average or below average in these areas. Pointing to his own research, Kaplan explained that this data is important because research in this area has shown that life expectancy health disparities are highly correlated with fourth grade math disparities.

He also highlighted his research findings from examining the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study, a U.S. national cohort study and pointed out that examination of the data finds that having less than a high school degree is associated with the shortest life expectancy. This relationship persists beyond college graduation, said Kaplan, emphasizing that even when the data is adjusted to account for various other demographic variables, this finding persists. Kaplan further explained that when it comes to the amount of health services used relative to educational attainment, the U.S. is an outlier in terms of the dollars spent. The U.S. is not necessarily getting better health outcomes. More important, the amount of health care used does not explain the variability in life expectancies among the various populations. Kaplan maintained that while additional research is needed in this area, countries that have experienced big improvements in the number of people with higher education have seen “enormous” increases in life expectancies.

Ryan Masters provided a historical look at the causes and nature of mortality in the U.S. He highlighted research by Patrick Krueger that uses federal data sources, including the National Health Interview Survey, Linked Mortality Files, and the American Community survey, to examine adult mortality and educational disparities in cohorts from 1925 through 1945. According to Masters, that research found that approximately 145,000 deaths could be attributed to individuals having less than a high school degree. Similarly, nearly 550,000 deaths could be attributed to individuals having educational levels less than a baccalaureate degree. Masters explained that Krueger’s research shows that that long-term historical forces are important when examining these phenomena, including revealing that in less than a generation there was a doubling of the impact of education. Social factors have an increasing importance in shaping the mortality in the U.S. and that as humans have progressed their long

Ryan Masters provided a historical look at the causes and nature of mortality in the U.S. He highlighted research by Patrick Krueger that uses federal data sources, including the National Health Interview Survey, Linked Mortality Files, and the American Community survey, to examine adult mortality and educational disparities in cohorts from 1925 through 1945. According to Masters, that research found that approximately 145,000 deaths could be attributed to individuals having less than a high school degree. Similarly, nearly 550,000 deaths could be attributed to individuals having educational levels less than a baccalaureate degree. Masters explained that Krueger’s research shows that that long-term historical forces are important when examining these phenomena, including revealing that in less than a generation there was a doubling of the impact of education. Social factors have an increasing importance in shaping the mortality in the U.S. and that as humans have progressed their long

evity have had less to do with “cruel fate, random accidents, and bad luck” and more to do with factors within human control such as “policies, knowledge, and behavior.” No other species have the ability to remove itself from randomness where the causes of death were concentrated in infancy, poor nutrition, infections, and parasites, he maintained.

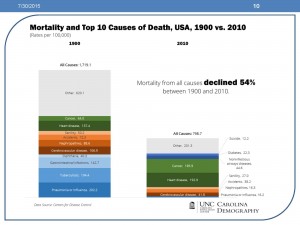

Masters also shared research that reveals that the “rate of technological and human physiological change” in the 20th century revolutionized “when we die, the causes of death and the overall health of the U.S. population.” Consequently, death has been concentrated to adulthood and is the result of factors associated with premature death, including health behaviors such as the lack of sleep, smoking, and diet, which are more difficult to manage. Education is an important tool in how to manage these factors. Human vulnerability has migrated so that it is now an individual-level matter, said Masters, noting that the mortality from all causes of deaths declined by 54 percent between 1900 and 2010.

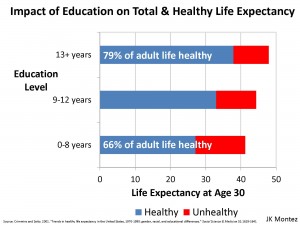

Jennifer Karas Montez shared her research findings that show a positive association between an individual’s educational attainment and their health and longevity, even when controlling for other social and economic factors. Montez emphasized that her results are based on data from federal data sources which find that educational attainment is “one of the strongest predictors of how long, and especially how healthy, we live.”

Jennifer Karas Montez shared her research findings that show a positive association between an individual’s educational attainment and their health and longevity, even when controlling for other social and economic factors. Montez emphasized that her results are based on data from federal data sources which find that educational attainment is “one of the strongest predictors of how long, and especially how healthy, we live.”

Specifically, she explained, research shows that at least one year of college is important in how healthy we live. Education provides access to resources that shape health, through economic (e.g., job, income, health care), social (e.g., relationships, friends, support), lifestyle (e.g., smoking, exercise, alcohol), cognitive (e.g., information processing, sense of control), and physiological mechanisms. Education may “alleviate the health consequences of being raised in adverse circumstances.” The “weight of the evidence suggests that raising educational levels is an important strategy for improving population health,” Montez concluded.

Vida Maralari stressed the importance of context and that education is a process. The “years of school completed doesn’t drop down on you in adulthood,” she noted. Education is a process across the life course and includes important aspects such as type of school and classes, quality of school and teachers, friends and peers in school, beliefs about the future, extracurricular experiences, early childhood education and “social and emotional” skills, and can be what you learned in preschool or in college. The impact of these factors can be direct and immediate in the short term or indirect and have a longer-term effect. For example, Maralari explained, an individual can get a college degree and as a consequence earn higher wages, or a child may attend a high quality preschool which improves pre-literacy skills. In the longer term, students can learn to solve word problems in the ninth grade, increasing their literacy skills, and are more likely to breastfeed, read to their child at age three, take medication as prescribed, and exercise after a heart attack. She also noted that increased levels of education also shapes your social relevance; for instance it can change such things like the stigma associated with smoking, being overweight, or giving soda or candy to a toddler.

Vida Maralari stressed the importance of context and that education is a process. The “years of school completed doesn’t drop down on you in adulthood,” she noted. Education is a process across the life course and includes important aspects such as type of school and classes, quality of school and teachers, friends and peers in school, beliefs about the future, extracurricular experiences, early childhood education and “social and emotional” skills, and can be what you learned in preschool or in college. The impact of these factors can be direct and immediate in the short term or indirect and have a longer-term effect. For example, Maralari explained, an individual can get a college degree and as a consequence earn higher wages, or a child may attend a high quality preschool which improves pre-literacy skills. In the longer term, students can learn to solve word problems in the ninth grade, increasing their literacy skills, and are more likely to breastfeed, read to their child at age three, take medication as prescribed, and exercise after a heart attack. She also noted that increased levels of education also shapes your social relevance; for instance it can change such things like the stigma associated with smoking, being overweight, or giving soda or candy to a toddler.

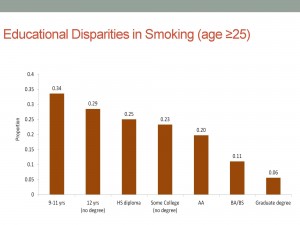

Maralari reiterated Masters and Montez in emphasizing that “modifiable behavioral risk factors are leading causes of mortality” in the U.S. These factors include smoking (18 percent of U.S. deaths in 2000), poor diet and physical inactivity (16.6 percent of U.S. deaths) and alcohol consumption (3.5 percent of U.S. deaths). Pointing to the educational disparities in smoking in individuals under the age 25, she noted that the more education that an individual has the less likely he/she smokes.

Maralari also emphasized the importance of large-scaled, longitudinal demographic data, which allows researchers to figure out how education shapes health and wellbeing. She also emphasized that education and health are intertwined across the life course and restated the need for longitudinal and detailed data on educational and health-related experiences and characteristics from childhood to adulthood in order to understand how educational policy can have health dividends. This includes data on both individuals and families, she concluded.